WHO ARE WE NOW

LAND ART MONGOLIA 5TH BIENNIAL

10 - 19 August, 2018

Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery

LAND ART MONGOLIA 5TH BIENNIAL

10 - 19 August, 2018

Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery

Globalisation can be understood specifically as an attack on cultures that are close to ‘nature’, or that continue to respect the values implicit in ‘nature’. What are these values? The attitude that humanity shares a delicately balanced habitat with other animals, and that the entire ecology deserves our respect. It is a holistic outlook, advocating sustainable rather than exploitative approaches to resources. This attitude, these ‘natural’ values, were present in early Humanism. What went wrong?

The balance between city-dwellers and rural populations tipped in the direction of urbanism. More of the world’s population is resident in cities than in the countryside, and this process continues to accelerate. It means that fewer and fewer people understand or value the complex and dynamic ecology of ‘nature’ as a set of values or a philosophical model. But urbanisation is only evidence of a more massive change both in the history of ‘humanity’ and in the history of ‘nature’. The narrative that describes the development of the natural world is the science of geology, since what we know about the long history of the planet has been mapped mainly through geology.

There is now a decisive body of evidence to show that the surface of the planet entered a new geological age around 1950, in the decade following the detonation of the first atomic bomb. This evidence comes from many sources: from records of radioactivity, of the use of fossil fuels, of pollutants, of atmospheric and climatic changes, and of the rate of extinctions of species of plants and animals.

The name given to this new age is the Anthropocene, from ‘anthropos’, the Greek word for human.We’ve entered the Age of Humanity, when the behaviour of humanity has become the dominant factor in the ecological balance of the planet.

The 5th Biennial is entitled: WHO ARE WE NOW ?

How do we situate art, and specifically art made in the Mongolian context, in relation to Humanism and the Anthropocene Age? The idea of a trans-cultural, or trans-national, or inter-national art is a Humanist legacy. Without a belief in the commonality of human beings, it would not be possible to make art that communicates beyond one culture by appealing to that which is shared by all humans.If we deny the legacy of Humanism, it means that whatever art we make will only ever be understood or appreciated by people from our own culture.

On the other hand, the Humanist legacy must be held responsible (along with militarism, empire-building, commercial greed and financial power) for producing globalisation and the Anthropocene Age. And these forces threaten each of the specific and unique geographic and linguistic cultures that have evolved over millennia, and that we value and recognise in different parts of the world. We are interested to open a discussion on human values today that will be shared in one of the most remote areas on the globe for a display at the Binennial venues of the capital Ulaanbaatar to enhance a mutual exchange on these issues.

Curator: Lewis Biggs

The balance between city-dwellers and rural populations tipped in the direction of urbanism. More of the world’s population is resident in cities than in the countryside, and this process continues to accelerate. It means that fewer and fewer people understand or value the complex and dynamic ecology of ‘nature’ as a set of values or a philosophical model. But urbanisation is only evidence of a more massive change both in the history of ‘humanity’ and in the history of ‘nature’. The narrative that describes the development of the natural world is the science of geology, since what we know about the long history of the planet has been mapped mainly through geology.

There is now a decisive body of evidence to show that the surface of the planet entered a new geological age around 1950, in the decade following the detonation of the first atomic bomb. This evidence comes from many sources: from records of radioactivity, of the use of fossil fuels, of pollutants, of atmospheric and climatic changes, and of the rate of extinctions of species of plants and animals.

The name given to this new age is the Anthropocene, from ‘anthropos’, the Greek word for human.We’ve entered the Age of Humanity, when the behaviour of humanity has become the dominant factor in the ecological balance of the planet.

The 5th Biennial is entitled: WHO ARE WE NOW ?

How do we situate art, and specifically art made in the Mongolian context, in relation to Humanism and the Anthropocene Age? The idea of a trans-cultural, or trans-national, or inter-national art is a Humanist legacy. Without a belief in the commonality of human beings, it would not be possible to make art that communicates beyond one culture by appealing to that which is shared by all humans.If we deny the legacy of Humanism, it means that whatever art we make will only ever be understood or appreciated by people from our own culture.

On the other hand, the Humanist legacy must be held responsible (along with militarism, empire-building, commercial greed and financial power) for producing globalisation and the Anthropocene Age. And these forces threaten each of the specific and unique geographic and linguistic cultures that have evolved over millennia, and that we value and recognise in different parts of the world. We are interested to open a discussion on human values today that will be shared in one of the most remote areas on the globe for a display at the Binennial venues of the capital Ulaanbaatar to enhance a mutual exchange on these issues.

Curator: Lewis Biggs

Akmar Nijhof NL

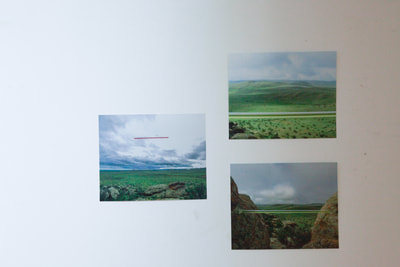

Akmar made two works from red flags (the same number of flags in each work). The first consists of a circle laid out on the green grass, with a diameter so large that it’s not easily viewed from one place. In fact its scale seems to relate more to the stride and pace of a horse than a human – it’s easy to imagine horses running around the circumference at the start of some celebration for which flags are brought out.

The second work, also made from red flags on green grass, stakes out from memory the footprint of her childhood home. This is a large irregular rectangular shape, not entirely flat, but its irregularities seem very much ‘at home’ on the edge of this escarpment overlooking a little stream and valley. Both works are abstract, geometrical, and for the artist both works carry an emotional connection and bodily memory from her childhood. Paradoxically it may be precisely their abstraction that enables them to communicate. |

|

Ana Laura Cantera ARG

|

|

Bat-Erdene Batchuluun MN

|

|

Batsaikhan Soyolsaikhan MNSoyolsaikhan Batsaikhan’s artwork combines installation and performance, and addresses the question ‚Who are we now as Mongolians in our own land?

The mirror represents self-scrutiny, the attempt to see oneself along the road to understanding oneself. The artist started by installing different sizes of mirror into the land, curved around, so that the person standing in the middle can see many different images of him or herself. This mirror installation then forms the backdrop for the performed part of the installation, in which Batsaikhan asks people to put on robes and join themselves to him through lengths of ribbon. In this way he can be connected to many people at the same time in his journey of self-reflection and questioning. |

|

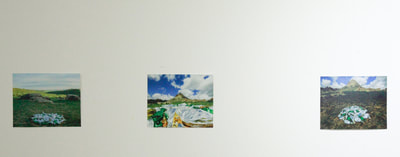

Camille Biddell UKCamille Biddell’s concern as an artist is to resist the homogeneity of mass production through the use of clay. She says ‘The repetition and rituals linked to ceramics are meditative, engaging and direct, values I find to be lacking from daily life, which is increasingly mediated through (digital) screens rather than tangible experience.’

The artist worked in a children's summer camp in Mongolia some years ago. Since in her view ‘ceramics often symbolise sharing and conversation’ it seemed a natural thing to organise a ceramics workshop for local people during LAM 2018. Her artwork was inspired by the way in which, as she says, a ‘landscape can trigger memories or déjà vu – sometimes when returning to a place the memories can be stronger than the present, like ghosts’. Memories and the present flow into what may be imagined memories, until the past, present and future merge. |

|

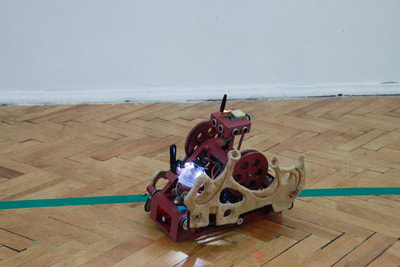

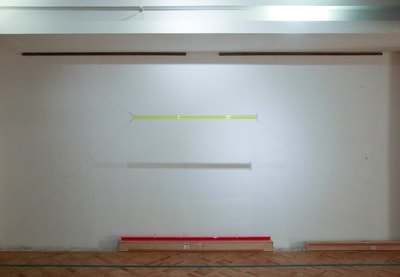

Junichiro Iwase CANLand Scale - ‘Let us measure nature with nature itself’.

Junichiro Iwase’s installation intends to open up conversations about the relationship between ‘human’ and ‘nature’ in our contemporary context of globalization. More specifically, this installation proposes an enquiry as to what it might mean to be ‘balanced’ in the age of the Anthropocene. It also throws into question how we can strike a ‘balance’, or more colloquially, 'level the playing field', whilst preserving a moral ecology that attends to the complexities and contradictions inherent in our relationship with ‘nature’. |

|

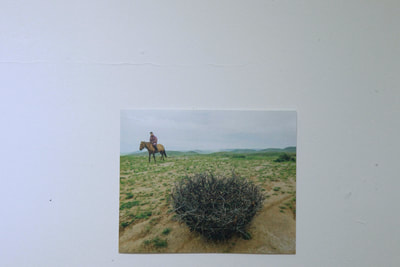

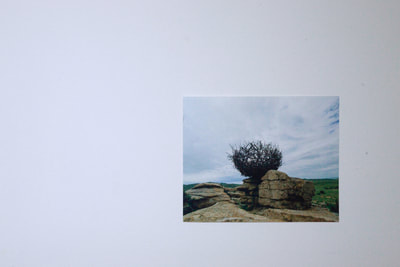

Jette Mellgren DKExploring around the camp site in Khentii, Jette Mellgren was followed closely by three eagles. She conceived the idea of making a nest ‘for’ these eagles, but to make it portable – a nomadic nest.

Her comment is that ‘A nomadic home stays the same inside while the landscape changes outside, when the household moves on. The ger is like a nest – a symbol of life, a place where you can feel confident and grow up safe. |

|

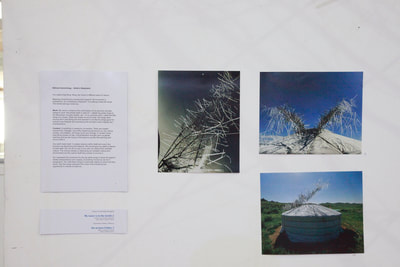

Zheng Lu PRCFor his artwork, Zheng set up lengths of adhesive tape stretched between rocks in the landscape and left them there to collect whatever was brought to them by the wind: visible and invisible, organic and inorganic fragments from the landscape, whether from hair from animals, feathers from birds, parts of insects, seeds, leaves, dust from the rocks, and maybe even dust from humans.

In this work it is the wind, a dominant element in the landscape, that becomes the ‘active principle’, moving particles around as humans are moved around the globe by forces that may be powerful but also invisible. The two-dimensionality of the collection of dust on the adhesive tape makes it like a drawing. When confronted by a two-dimensional recording, are we able to imagine a full life in three dimensions? Zheng’s attention to the inconspicuous is a way to pay acknowledge and respect the diversity of unique particles that together go to form the landscape. |

|

Mariko Hori JP/SRBMariko Hori’s Fishing for the Earth constructs the image of a solitary person in conversation with the earth through the instrument of a fishing line. As she says: ‘The fishing-line would break if you tugged too strongly. It is necessary to keep the balance and feel the weight of the earth. Then, you will know that you can never ‘catch’ it.’‘Lack of communication foments this unbalanced relationship between humankind and nature. It’s time to talk to the earth again.

In her second work, The Future is Made from Something Floating, Hori wanted to celebrate ‘the atmosphere and spirits’ of the place, made up, as she says, ‘from everything which has existed here until now.’ And that includes contributions from the bodies of humans passing by in the present as well as those that have passed by in the past. She imagines people in the future feeling the presence of her own contribution. |

|

Megumi Shimizu JPThis work emerged from her feeling about the Fukushima nuclear meltdown after the tsunami of 2011. The Japanese government collected and stored the contaminated soil and prohibited contact with the soil. The community between human beings and the soil was destroyed.

Shimizu had the idea that the soil should be allowed to move again. So she used the local soil to dye fabric (and then removed the radiation) – the colour of the mud staying in the material. A corresponding process in Mongolia meant that white fabric was dyed with local soil, and both fabrics were made into flags. |

|

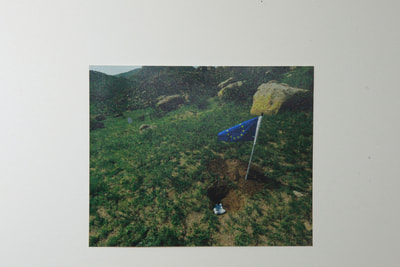

Michele Giacobino ITThe title Club refers instead to the ‘club’ of G20 nations (20 of the nations with ‘developed’ or more powerful economies) whose attitudes largely determine the use of natural resources – including the land - around the world.

So, in Club, the use of the flags of the twenty nations refers to the globalized culture of the G20. As Giacobino points out, the homogeneity of globalized culture leads people to seek out the unusual, ‘exotic’ or ‘undeveloped’, adjectives often applied to Mongolia. Since there are also artists from almost 20 nations (not G20) in this edition of Land Art Mongolia, come to experience the land and its people, Club can also be understood as a reflection on the artists and Biennial workshop. Flags are an ambiguous device, of course, referring not simply to the marker of the golfer’s ambition, but also to the territorial ambition and claims of nation states to possess the land. |

|

Odmaa Uranchimeg MNOdmaa Uranchimeg‘s artwork for LAM 2018 is a pair of big white wings that can be attached to a ger.

It follows a previous work, in which she attached a small pair of wings to a sheep. When the sheep moved, the wings moved too, as if the sheep was flying. She felt that the wings gave the animal more freedom and expressed its innate majesty and characteristics. Everything is created by movement. There are unseen movements, changes, and shifts happening all around us. Our nature, society, and tradition, all things move and change. In modern times, everything moves so fast. Industrialization brought upon us global warming and we are trying to find ways to counter the warming and survive with it.’ |

|

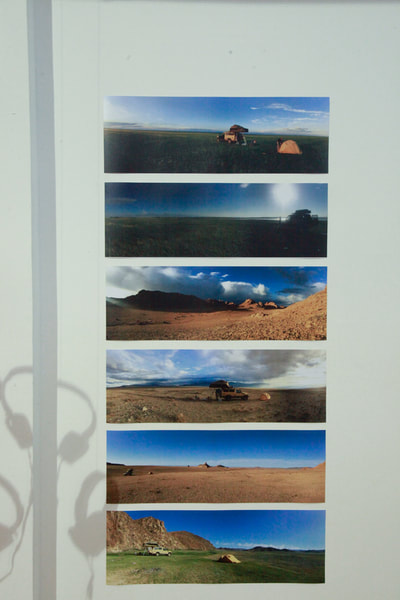

Elizabeth Prins ZAF/TWNElizabeth Prins’ engagement with the land took the form of building a movable survival shelter; then taking the shelter for a walk; and recording some impressions – visible and invisible – that were found on the way. The entire sequence had a ritualised and performed aspect, inducing a kind of self-awareness in the people around the artist (the audience for this land art).

Prins says ‘I utilize and appropriate found objects, concepts, lyrics and techniques - inviting the audience to move within or around a space of speculation.’ The strangeness of a lone walker armed with a geiger counter taking an inverted bath tub through the grassland was certainly an invitation to re-frame the landscape and speculate as to what hidden knowledge it might reveal. In general, Prins uses her work as a means to develop her understanding through ‘recalibration’(as she calls it), a process that for her also involves making material objects. |

|

Richard Jochum USARichard Jochum’s installation Rock Candy consists of an assembly of stones, gift-wrapped in blue, green and silver foil. The stones, found on the site, are arranged in a circle. The artist imagines a hungry walker happening on the artwork - by offering a shot of sugar when it’s most needed, Rock Candy offers a gift, albeit one that can be consumed only visually.

The project plays with the idea that things are not always what they seem through the ironic use of materials ⎯ the stones are being protected, not the people. At first glance, Rock Candy seems out of place in the environment, an intrusion of coded consumerism into the unmediated landscape. On further reflection, it plays on the reverence accorded to the elements of the landscape, and especially stones, by Mongolians, and suggests that the landscape is itself making a welcome offering to the walker. |

|

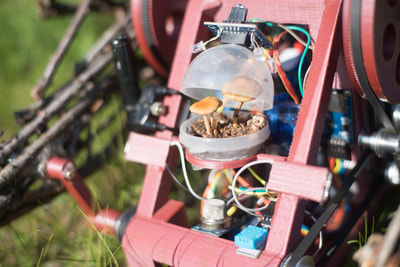

Ronald van der Meijs NLThe instruments are part of the installation where the natural elements of the steppe location bring it to life and determine a sound composition to the rhythm of nature. While placing these instruments to the elements, it will show similarities - the resulting composition of pitch and tone that the instruments are capable of. A response similar to that of people with their environment. Here modern solar panels and traditional materials go hand in hand in order to pitch and sound. Holding it all together with a construction derived from various nomadic tent constructions that I investigated during the journey. Here the modern and traditional go hand in hand in order to achieve a universal language for humanity. While the natural elements of the steppe are conducting this installation on the rhythm of nature.

|

|

Sena Park KR/NZThe artwork represents an urbanite fantasy or projection about living ‘in nature’. She has installed the artificial and decorative signifiers of urban and domesticated living into a landscape that is…certainly not domesticated.

Park hopes that her artwork might be understood as an ironical comment on the (impossible?) dream of a ‘perfect life’ that balances nature along with the comforts and intelligent technology of urban living. |

|

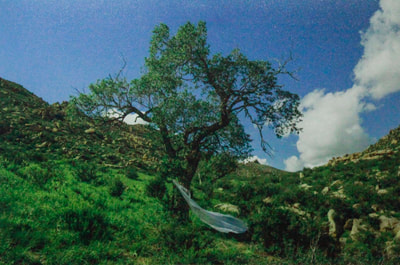

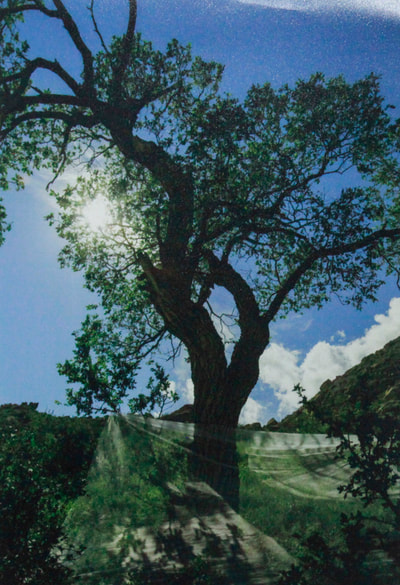

Shirin Abedinirad IRNShirin’s work for LAM re-contextualizes elements that were once adapted and adopted from East Asian traditions into Iranian art. A sheet of transparent white fabric placed around a tree catches the shadows cast by the branches as the tree moves in the wind. The wind catches the screen also, and its movements form a counterpoint to those of the branches above, creating a dance choreographed by nature.

The artwork provided the artist with an interaction with the environment in a rhythm of repetition and continuity. Her viewpoint is that of the audience, with nature as the performer: a merging of her subjectivity with that of the surrounding natural world. As she says: ‘I am involved in a silent dialogue with nature; a dialogue with a mighty presence that was beholding me.’ |

|

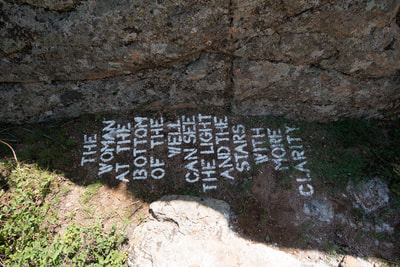

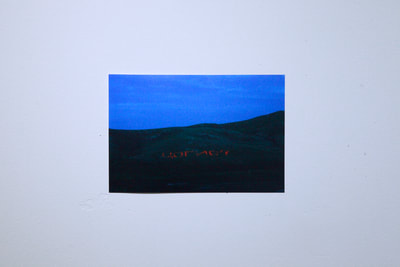

Sophie Guyot CHGuyot’s art is concerned with how the words we use reflect and inform our views – how language forms our view of the world. This work for Land Art Mongolia 2018 started with a series of informal conversations between Guyot and people from different and distant cultures: the artists of the biennial gathered in Murun Sum, Khentii - who come from all over the world - and the inhabitants of the region, with a culture that still bears many traces of nomadism.

Although her personal focus in these conversations was to explore the idea of humanism in the Anthropocene age, she found a deeper personal connection with people through her love of horses, and the fact that horses play a central role in Mongolian culture. In fact, the figure of the ‘horse’ began to represent all the depth and range of meaning of the figure of the human, a kind of alter ego. The question mark that follows the word is important: it focuses on the interaction between the installation and those present, questions them directly and invites them to take a stance. |

|

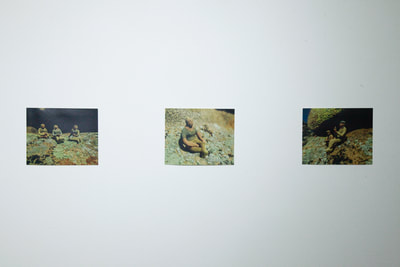

Tanya P. Johnson ZAF/CANThe Anthropomorphs created thereafter are inspired by the ancient Mongolian mythical and supernatural winged bird-humans called the Galbinga. They have assembled from found and natural objects. The integrated musical instrument parts are symbolic of vehicles for story.

My inspiration for this work (is layered, of course) comes from my perception of the cosmologies and ways of expressing relationship with the unseen that I have witnessed in Mongolia. This includes offerings seen in the temples, milk offerings and the knowing of, but as yet not experienced, practice of Shamanism. |

|

Tetsuo Jamashige JPPeople in Japan believe that there is a holy spirit that lives in stones, trees and all other things; this has been a part of Shintoism and folk belief since ancient times.

We call it ‘Tsukumogami’ or ‘Yaoyorozu no Kami’ (eight million gods), meaning that people appreciate and respect long-lived objects. These are the experiences resulting in the land art documented in the exhibition – a video, drawings and an installation in the landscape by Mega’s family. The artist’s collaborators were Gantumur Magsarjav & Saruul Choijamts; Maygmarsuren Dashdorj & Saranchimeg Surenkhor; Gegeenkhusel Khishigbaatar & Bayasgalan Batsaihan, assisted by Satoko Tokashi. |

|

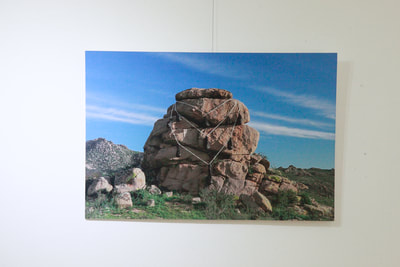

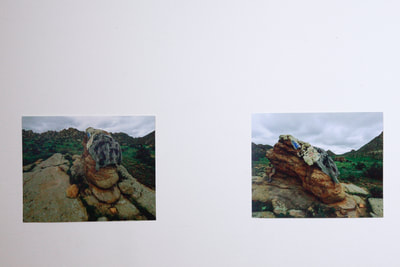

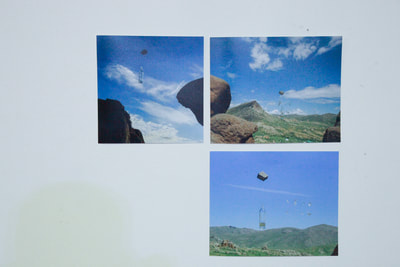

Vikram Divecha IND/UAEVikram Divecha’s Mala (garland in Hindi), responds to a particular landscape in Mongolia. Drawing from the Eastern ritual of garlanding idols, the artist has embraced the land with a mala. A monumental 8-meter high granite rock formation emerging in the valley near the Land Art Mongolia (2018) camp, was the artist’s chosen site for enacting this ritual. The mala was strung with sacks of coal, bringing into conversation the changing relationship between people and land.

Expressing gratitude for what Mother Earth has bestowed upon one, a mala is often strung with offerings - at times sources of energy one lives upon, such as edible items. For ‘Mala’ the artist has made an offering of a relatively new source of energy in human history - coal. This gesture highlights the resources on the land (including that of welcome) and those underneath - one, which tends to replenish, the other, not. |

|

Siou Ming Wu TWNThe artist posed the question, therefore, whether plants might discuss environmental issues themselves? Initially he imagined a conference of plants, later reduced to just two plants in discussion (male and female). Their conversation touches on the environment, survival, satire, fear and death, expressing their anxiety and helplessness toward the contemporary world, and becoming an argument that will not stop.

If plants were really able to talk to humans, then what kind of position would they place humans in? Science has made progress in understanding how plants communicate with each other, but has not yet managed to decode the content of communication. We are quickly growing an ‘internet of things’, but wouldn’t it be a great idea to grow an internet of plants? |

|

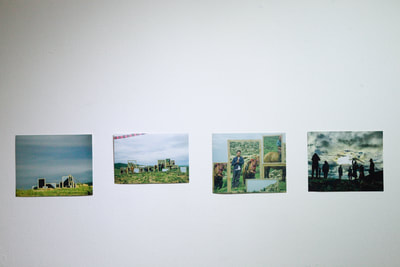

Munkhjargal Jargalsaikhan MNJargalsaikhan set up a ‚time frame‘, similar to a photographers‘ ‚set‘, in the landscape to show the transition from Nomadism to Urbanism. The representation of living in the endless landscape is left behind, outside the frame, so that these Mongolians can live in the newly constructed world. This time frame ‚room‘ represents the constructed world that changes how people think and experience their lives. In the portrait, the box masks that people wear are intended as a comment about ‚brainwashing‘ new Mongolians.

|

|

Text by Lewis Biggs & Solongo Tseekhuu

The participating artists:

Dinh Q. Le VNM

Mee-Ping Leung HKG

Oswaldo Macia COL/UK

Jette Mellgren DK | L

Rirkrit Tiravanija THA/USA

Allard van Hoorn NL/USA

Dinh Q. Le VNM

Mee-Ping Leung HKG

Oswaldo Macia COL/UK

Jette Mellgren DK | L

Rirkrit Tiravanija THA/USA

Allard van Hoorn NL/USA

Exhibition Details

Title: WHO ARE WE NOW - LAND ART MONGOLIA 5TH BIENNIAL

Address: Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery

Dates: 10-19 August, 2018

Opening Hours: Monday to Friday, 10am to 5pm

Admission: Free

Travel: South from the Sukhbaatar square across Peace Avenue

For press information and images contact:

Email: [email protected]

Title: WHO ARE WE NOW - LAND ART MONGOLIA 5TH BIENNIAL

Address: Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery

Dates: 10-19 August, 2018

Opening Hours: Monday to Friday, 10am to 5pm

Admission: Free

Travel: South from the Sukhbaatar square across Peace Avenue

For press information and images contact:

Email: [email protected]