documenta 14

10 June- 17 September, 2017

Kassel, Germany

documenta 14's exhibition in Kassel opens its door to public on 10 June, 2017.

SHARAV Balduugiin

(1869–1939)

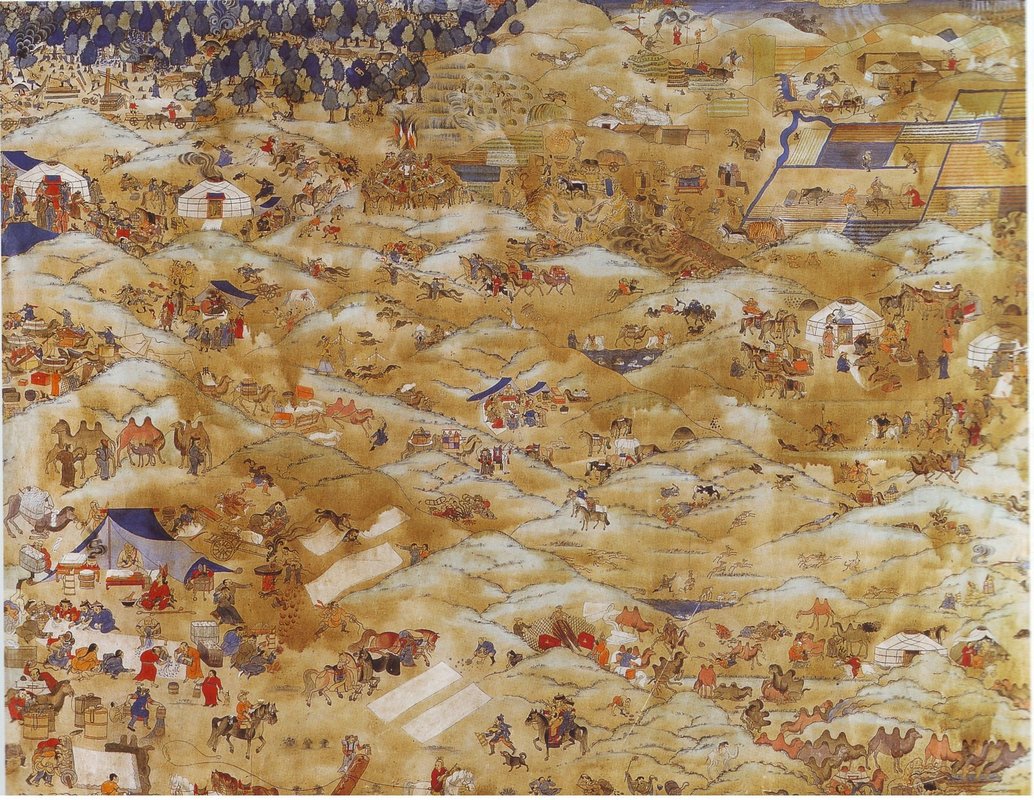

As legend has it, the Tibetan-born reincarnate ruler Bogd Khan (1870–1924) commissioned the famous artist Baldugiin Sharav to paint scenes representative of life in the Mongolian countryside during the first years of the Khan’s theocratic rule over Mongolia. With the assistance of other artists, Sharav created two paintings that were initially titled Daily Events, but now have been renamed One Day of Mongolia (Autumn)—on display here—and Airag Feast. The paintings are emblematic of the Urga School of painting—a style of Mongolian painting of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that sought to preserve the traditional elements of folk painting and was characterized by narrative compositions with straight-forward, colorful depictions of events free from strictly religious subject material, while often infused with parody and exaggeration. In the year 2017, One Day of Mongolia (Autumn) exists as both a frequently reproduced icon of national identity and an image of rural life that continues today only outside of Mongolia’s sedentary urban centers. Winter Palace, rumored to be painted by Sharav as well, depicts the Khan’s winter palace as an important center for agriculture and trade, as well as some scenes of debauchery. Arguably, the rumors and potential scandals around the authenticity of the paintings as well as their attribution to Sharav (who continued to be a socialist realist painter in the socialist Mongolian People’s Republic until his death), only adds to their status as national and cultural icons.

WorksBaldugiin Sharav (attributed)

(b. 1869, Mongolia; d. 1939)

One Day in Mongolia (1912–13, provenance not verified)

Mineral pigments on cotton

177 × 138 cm

G. Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Neue Galerie, Kassel

Baldugiin Sharav or an artist of the Urga School

Winter Palace (1912–13)

Mineral pigments on cotton

188 × 178 cm

Bogd Khaan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Neue Galerie, Kassel

(b. 1869, Mongolia; d. 1939)

One Day in Mongolia (1912–13, provenance not verified)

Mineral pigments on cotton

177 × 138 cm

G. Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Neue Galerie, Kassel

Baldugiin Sharav or an artist of the Urga School

Winter Palace (1912–13)

Mineral pigments on cotton

188 × 178 cm

Bogd Khaan Palace Museum, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Neue Galerie, Kassel

NOMIN Bold

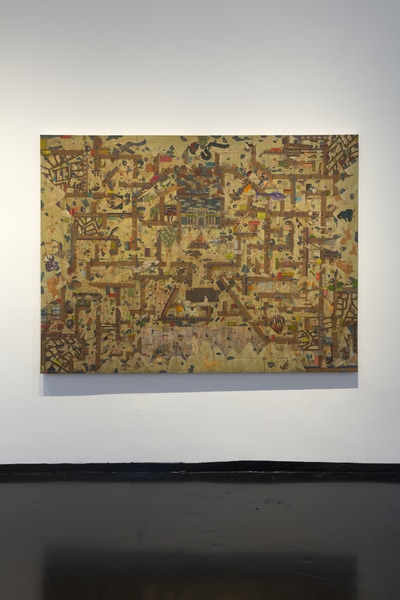

Nomin Bold belongs to the new generation of Mongol Zurag (literally, Mongol Picture) artists, who were trained after the socialist restrictions on tradition were lifted in Mongolia, just as the country was transitioned in 1990 into democratic governance and a market economy. Nomin, born in 1982, graduated from the class of “Mongol Zurag” in the newly opened division of “National Art” at the only public, state-run College of Fine Art in Ulaanbaatar. She and her classmates, together with their teachers, began the process of shaping and conceptualizing what Mongolian tradition means in a globalized world, in which Mongolia is striving to claim its own distinct place.

The concept of Mongol Zurag was developed by Mongolian art historian Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem (1923–2001) during the heyday of the country’s twentieth-century socialist regime. The Mongol Zurag was an “invention of tradition,” as British historian Eric Hobsbawm would have termed it; a strategy to preserve the cultural identity of Mongolians vis-à-vis the Socialist Realism that was imported into the nation and reinforced by its Soviet instructors. During the socialist period in Mongolia (1921–1990), the USSR and Eastern Europe were the windows onto the world, and the only channels through which European art media, such as oil painting on canvas, was introduced, quickly replacing Buddhist art traditions.

Nomin’s works are distinct for their subtle yet vibrant colors, meticulous drawing, and somewhat mysterious subject matter. Her frequent use of lone female figures as the single compositional element suggest, on the one hand, her interest in situating women as the key players in any environment; while, on the other hand, the national costumes (long discarded in Mongolia) or modern clothing worn by the figures offer a glimpse into the question of the relationship between modernity and tradition that the artist is struggling to understand and raising for individual interpretations.

Buddhist imagery in Nomin’s art serves as motifs and symbols of past traditions, now placed amid the contemporary realm of superfluous commodification. While the artist takes into account the intrinsic Buddhist meaning that she selectively brings into her works, it is rather her inquiry into the nature of the tradition itself and how it can be juxtaposed, superimposed, or envisioned in the modern world that motivates and inspires her unusual compositions. Such queries and inspirations imbue the art of Nomin with a mystery that demands inquisitive and unfaltering attention.

—Uranchimeg Tsultemin

The concept of Mongol Zurag was developed by Mongolian art historian Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem (1923–2001) during the heyday of the country’s twentieth-century socialist regime. The Mongol Zurag was an “invention of tradition,” as British historian Eric Hobsbawm would have termed it; a strategy to preserve the cultural identity of Mongolians vis-à-vis the Socialist Realism that was imported into the nation and reinforced by its Soviet instructors. During the socialist period in Mongolia (1921–1990), the USSR and Eastern Europe were the windows onto the world, and the only channels through which European art media, such as oil painting on canvas, was introduced, quickly replacing Buddhist art traditions.

Nomin’s works are distinct for their subtle yet vibrant colors, meticulous drawing, and somewhat mysterious subject matter. Her frequent use of lone female figures as the single compositional element suggest, on the one hand, her interest in situating women as the key players in any environment; while, on the other hand, the national costumes (long discarded in Mongolia) or modern clothing worn by the figures offer a glimpse into the question of the relationship between modernity and tradition that the artist is struggling to understand and raising for individual interpretations.

Buddhist imagery in Nomin’s art serves as motifs and symbols of past traditions, now placed amid the contemporary realm of superfluous commodification. While the artist takes into account the intrinsic Buddhist meaning that she selectively brings into her works, it is rather her inquiry into the nature of the tradition itself and how it can be juxtaposed, superimposed, or envisioned in the modern world that motivates and inspires her unusual compositions. Such queries and inspirations imbue the art of Nomin with a mystery that demands inquisitive and unfaltering attention.

—Uranchimeg Tsultemin

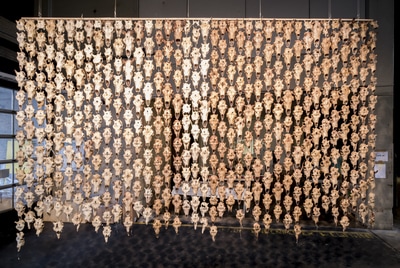

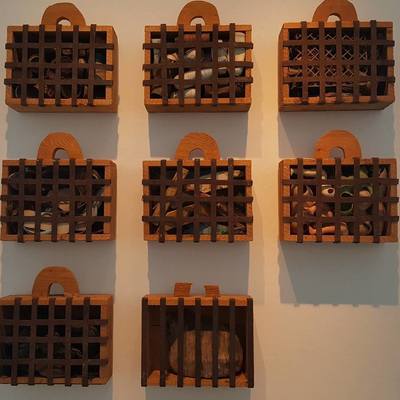

ARIUNTUGS Tserenpil

When I stepped into Ariuntugs Tserenpil’s studio, I thought that I had entered a little workshop or laboratory. There were a number of wooden tables and stacked pallets full of tool kits, wires, and wood; glues, paint, and tape; a drill and even a telescope. As usual, the artist greeted me with a quiet smile and invited me to sit on the couch. We discussed his latest works—moon recordings through a telescope and some other photographic experiments—and then watched a few of his early videos. Close observation of nature and objects and the use of everyday sounds are important elements of his video work. Ariuntugs often distorts the real look of the images through blurry records or negative effects.

Ariuntugs went on to tell me about his childhood habits (he was born in 1977 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia), how he liked dismantling toys and other assembled items, and the strange feeling it gave him to leave them disassembled. I thought about how this early behavior might relate to his approach as an artist—his minimal, monotonous works convey ambiguity, an odd coexistence of tranquility and disorder.

When I asked about his future plans, since his having been invited to documenta 14, Ariuntugs said something that might unsettle ambitious people: “For my artworks I don’t really make serious plans; I just do my work when I want to. I really like the process, but not the final result. I don’t really strive to show my work to people. The feeling I get from the process is important for me. Showing my work is a different kind of process for which I have to prepare. Different times and spaces always create different perspectives.”

Before I left the studio, we watched the video Act (2013), in which Ariuntugs chews moss and spits. When I asked why he decided to eat moss in the work, he said: “Personally, I always feel helpless watching how we human beings destroy nature to satisfy our ever-increasing consumption. We all act as if we have no choice but to consume more and more. One day I was looking at the moss I collected from the forest and suddenly thought, What would it be like if I eat moss? I tried to eat it and recorded my act. The taste was really awful.”

—Gantuya Badamgarav

Ariuntugs went on to tell me about his childhood habits (he was born in 1977 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia), how he liked dismantling toys and other assembled items, and the strange feeling it gave him to leave them disassembled. I thought about how this early behavior might relate to his approach as an artist—his minimal, monotonous works convey ambiguity, an odd coexistence of tranquility and disorder.

When I asked about his future plans, since his having been invited to documenta 14, Ariuntugs said something that might unsettle ambitious people: “For my artworks I don’t really make serious plans; I just do my work when I want to. I really like the process, but not the final result. I don’t really strive to show my work to people. The feeling I get from the process is important for me. Showing my work is a different kind of process for which I have to prepare. Different times and spaces always create different perspectives.”

Before I left the studio, we watched the video Act (2013), in which Ariuntugs chews moss and spits. When I asked why he decided to eat moss in the work, he said: “Personally, I always feel helpless watching how we human beings destroy nature to satisfy our ever-increasing consumption. We all act as if we have no choice but to consume more and more. One day I was looking at the moss I collected from the forest and suddenly thought, What would it be like if I eat moss? I tried to eat it and recorded my act. The taste was really awful.”

—Gantuya Badamgarav